The Magill Tragedy

The Magill Tragedy (1892)

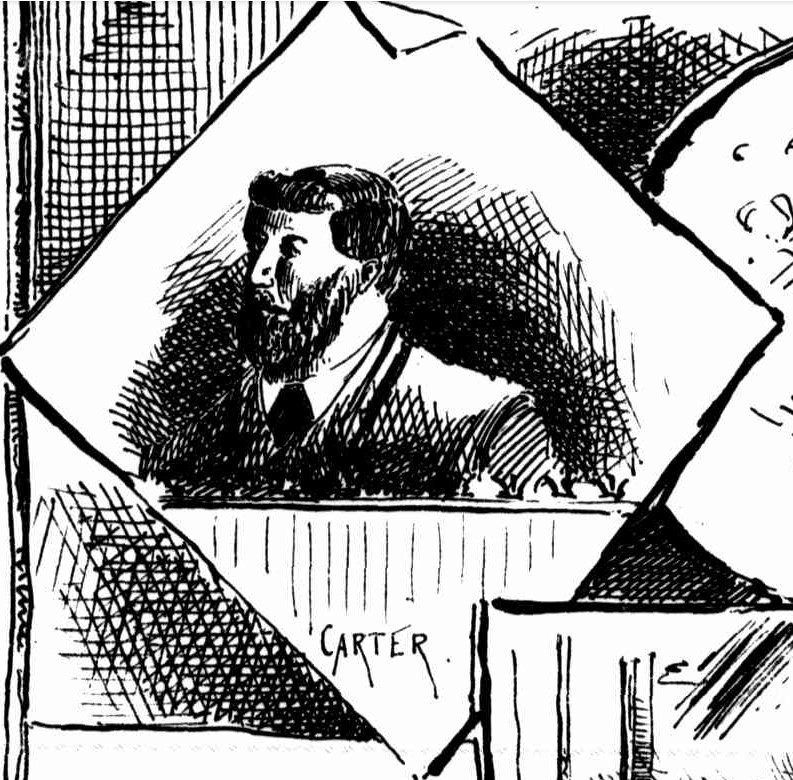

Shortly after midnight on Tuesday the 21st of June 1892, a terrible tragedy occurred at Magill. William ‘Scotty’ Edwards, a local stone cutter, was shot dead. The alleged murderer was a militia man (reserve soldier) named Joseph James Carter, who had attended the review of militia infantry at Montefiore Hill to commemorate the Queen’s Accession Day public holiday the previous day. He arrived home between 4 and 5 o'clock in the afternoon, had his tea (evening meal), then headed back to the city. After visiting several hotels, he returned to Magill shortly before 10 pm.

Upon his return, he met Edwards, who had left home at about 7.20 pm to borrow a pick and shovel from an acquaintance, Mr. Badman. The two men visited the World's End Hotel, Pepper Street, Magill, around 10 o'clock, where they had a drink, and then went to the East Torrens Hotel (now The Tower Hotel), Magill, a little further up Magill Road. While there they had some drinks with a third person called Collett, and an argument arose over some stray animals. Carter told Edwards that he intended to shoot some goats and dogs which had annoyed him by over-turning his meat safe. Edwards replied that it would not affect him, because he had neither goats nor dogs. The landlord of the hotel, Mr. Oliver, asserted that he was in the bar the whole of the time, and that no threats were made while the men were there. He said that at twenty minutes to 11 o'clock they had a parting drink and left in what appeared be perfect friendship. He added that Carter had consumed only three glasses of beer in the East Torrens Hotel.

After leaving the hotel, nothing more was heard of the principals of the tragedy until about 11.30 pm, when they were heard outside Edwards' house in Brougham Street, Magill, quarrelling. Annie Paulina Edwards, the wife of the murdered man, stated that when she had retired for the night she heard her husband speaking to someone in a loud tone of voice. She heard a strange voice say to her husband, “Bring the boy out, and I’ll be satisfied.” It appears that the meat safe issue was still bothering Carter, and although it is unclear what Carter intended to do to the child, her husband understandably replied that he would not, as his eight-year-old boy was asleep. She then got up, went outside, and recognized the stranger as Carter. Carter continued speaking to Edwards, “Then I'll take it out of you”, and hit the deceased, who returned the blow. The accused fell, and in doing so, grasped Edwards by the neck and tore his shirt. Mrs. Carter then arrived and asked her husband to go home, but with a bruised face and a vindictive spirit, he refused to leave until he had dealt with the deceased. Mrs. Edwards then asked Carter to leave her husband alone. He replied, “No, I won't. You go inside, you have no right to be out here”. He once again struck the deceased, who again retaliated, resulting in Carter falling.

Carter was then taken to his house in Marlborough Street, Magill, about 200 to 300 yards away from Edwards’ house [unable to identify this street – the location may have been deliberately obscured], supported by his wife and Edwards. On reaching his house, Carter said to Edwards, “I will meet you tomorrow night”. Mrs. Edwards had returned to bed, her husband then arrived home about ten minutes afterwards. In the meantime, Carter, somewhat worse for wear after the fist fight, was eager for retribution. In his drunken, possibly concussed delirium, he was unclear about where Edwards lived, so he then woke his eight-year-old son, Henry ‘Harry’ Carter, and asked the boy to direct him to the Edwards’ house. Harry had seen his father drunk before, but never as inebriated as he was on this occasion. He obeyed his father, and they set off towards the house, Carter suggesting to his son, “We will make out that we are shooting possums.”

At midnight, when Annie Edwards and her husband were retiring, there came a knock at the door, and a childish voice said that his father wanted Mr Edwards out in the road. Edwards advised the little boy to take his father back to bed, and after some words with Carter, went back inside. Carter decided to return home, but he was not in the mood for sleep. He asked his wife to give him a cartridge and when she refused, he intimidated her at the point of his bayonet. She subsequently got the cartridge out of the clothes box, and handed it to her husband, who proceeded to load his rifle for the return visit to the Edwards’ house. As Carter walked with his son, he said to the boy, “This is going to be a sorrowful affair, try to be a good boy to your mother, for you won’t have a father much longer.”

Edwards and his wife had once again retired for the night, when they were disturbed by the sound of a stone falling on the roof, and then a knock was heard at the door. Edwards knew Carter had returned, so he said to him, “You go away, and let me go to sleep.” Carter refused to do so saying, “No, I won't. You great coward, you're afraid to face it. You're too lazy to work, the Government has to keep you.” His abusive rant worked. Edwards got up, went to the front door and opened it, whereupon Carter said “I have got something for you”. Mrs. Edwards then heard Carter say, “Take that”, before he discharged his gun and shot him through the heart.

As Edwards fell he gasped out, “Oh Annie, I am shot.” Mrs. Edwards hurried to the door and saw Carter standing there, whilst her husband appeared to be sitting against a cot just between the door and the bedroom. She touched him on the head and said, “No Bill, you ain't dead,” but got no answer. In her bare feet, she then realised she was standing in a pool of her husband’s blood, causing her to scream in terror and run to her next door neighbour, Mr. Sandfead. She told him, “Mr. Carter has shot my husband.” Sandfead dressed and entered the house, where he saw Edwards in a sitting position beside the cot in the front room with his head hanging forward, quite dead. There was a great deal of blood about the floor. He sent for a doctor and did what he could in the meantime. He did not see Carter, as the night was very dark.

The report of the firearm was heard by Mr. William Hughes, a butcher, whose shop was on Magill Road about 100 yards from the scene of the shooting. He heard the report, and also a scream, at about 12.35 pm. Shortly afterwards two neighbours living in the immediate vicinity hurried to his residence and informed him that ‘Scotty’ Edwards had been shot. Mr. Hughes dressed hurriedly, got a horse, and rode to Dr. Shepherd’s house in nearby Maylands, who answered his summons immediately. Mr. Hughes then went to the Norwood Police Station [The Magill Police Station commenced operations in 1898] and reported the occurrence, the officers there in turn apprising the Metropolitan Police Station. Hughes then returned to the scene of the crime where he found Edwards' body in a sitting position, shot through the heart, the blood having streamed all over the place. “It was truly a horrible sight,” added Mr. Hughes. He did not touch the body, but waited until the police arrived. At about 3 am, Detective Lawton, Plain-clothes Constable Garland, and Mounted-Constable Whitters arrived at the house and took charge of the body. Detective Lawton then went to Carter's house, where the back door was open and a candle was burning. Carter was covered up in bed, asleep, with his grey uniform on. He woke him and placed him under arrest.

The accused did not say anything when charged and cautioned. He was evidently suffering from the effects of alcohol, and a few abrasions on the face showed that be had been fighting. A regulation rifle used in the South Australian Militia was found in the bedroom behind a child's cot in the room where Carter was sleeping, and it showed signs of having been recently discharged. Carter was subsequently taken to the Metropolitan Police Station, and locked up at 4.35 am.

The accused was 5 feet 9 inches in height, 30 years old, and to the residents of Magill he always seemed a ‘quiet sort of man’ and not at all quarrelsome. Edwards, of slightly smaller stature, and 29 years of age, was described by Mr. Oliver, of the East Torrens Hotel, as a decent sort of fellow. Mrs. Edwards was left with three small children, and general sympathy is felt for her in her great affliction. The affair threw the whole of Magill and the surrounding district into a state of alarm, and as soon as the news spread people began to flock to the neighborhood.

On Friday, the 5th of August, the case against Joseph James Carter concluded.

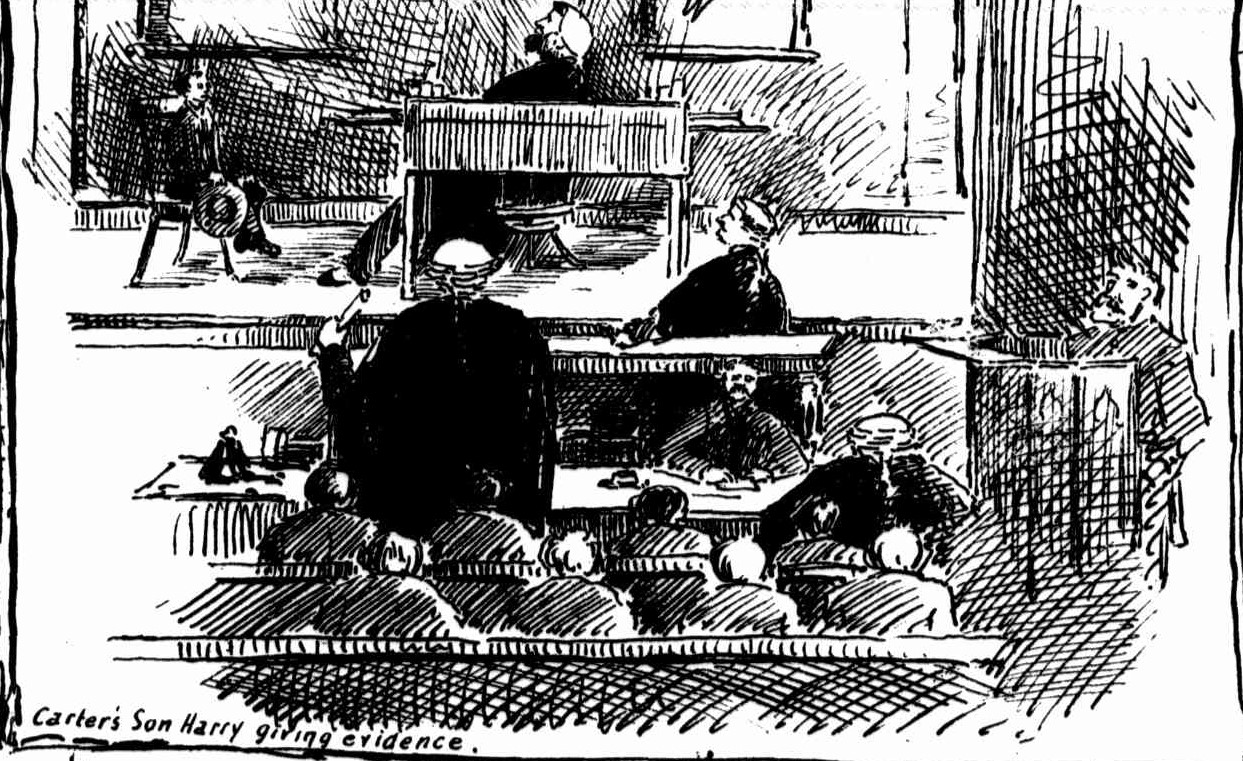

There was no conflict of testimony and the chain of evidence was most complete. It was conclusive not only as to the commission of the tragic act, but also as to its premeditation. The principal witness against Carter was of course his own son. It is difficult to imagine anything more distressing or pathetic than the relationship in which those two stood in the Court. Every word that the boy uttered was like a nail in his father's coffin. Step by step, unfalteringly, unconsciously yet pitilessly, he told the tale of his parent's crime. The fact that he should have to give evidence deciding the prisoner's doom was in itself sad enough. But the lad's utter lack of appreciation of the seriousness of the position made it all the more pitiful. He thought no more of his father going out to shoot a man than any other person would of a sporting excursion. No-one could have described what he saw more pointedly and lucidly than did this boy. Indeed, no grown up person could have told the same story in the same cool and collected way – they would have too keenly realized the weighty issue that hung upon their words.

Young Harry Carter also shed some light on the origins of the meat safe issue. Sometime before the shooting, he was with Edwards’ son William, who saw the meat safe and claimed that it was their property. Harry replied, “It ain’t”, and although he declared that no more was said, his father appeared to have some knowledge of the boys’ exchange. This is possibly why Carter initiated the argument in the East Torrens Hotel, and it may explain why Carter asked Edwards to bring out his son when he confronted him at his house.

The Judge began his summing up at 5 pm that day and also read the evidence, as is customary in murder cases. Carter's demeanor throughout was self-restrained and calm. He watched the proceedings throughout with the utmost attention, but gave no sign of the state of his feelings. The Jury took thirty-five minutes to consider their verdict. It was generally thought that the verdict would be one of manslaughter, but the Jury returned a unanimous verdict of willful murder. His Honour asked if there was any recommendation for mercy, but the foreman said, “We did not make one.”

The Judge then addressed Carter. “Joseph James Carter, you have been found guilty of the most heinous crime in the calendar. After a most patient and careful investigation the jury have not found their way to give you the benefit of any extenuating circumstances, so as to reduce your crime from that of murder to the lesser crime of manslaughter. I am bound to say I am not surprised that they have not been able to find those circumstances. Looking at all the surrounding circumstances of the case you stand in an extremely painful position, and I think your case stands alone in the annals of this or any other country in respect to the manner of the evidence which has brought about your conviction, a conviction brought about by the testimony of your own son, your own child, who you took to be a witness of your dreadful deed. You told him he would soon be without a father, but whether that will be true rests with another power, not mine. I do not wish to say anything that may add to the sufferings, which, if you have a conscience, you must experience. You were a member of the Volunteer Force of this colony, you wore its uniform, and by virtue of your position you undertook to protect your country from its foes, but you turned the weapon with which you were armed upon one of its peaceful citizens, and in a willful way deprived him of life. Under those circumstances I am not astonished that the gentlemen of the jury have been unable to find any extenuating circumstances. I can add nothing further. My painful duty now is to pass the sentence upon you which the law imposes. The sentence of this court is that you be taken to the prison from whence you came, and that you he hanged by the neck until you be dead, and that your body be buried within the precincts of the prison, and may God have mercy on your soul.” Carter never flinched when the Jury decided against him. He heard his sentence with unmoved countenance, and passed out of the dock with a steady step.

Carter’s fate appeared to be sealed, but luck was on his side. On Monday, August 22nd, a petition signed by 2,026 people was presented to the Executive Council, asking for a commutation of the sentence. It asked that the extreme sentence might be commuted for the following reasons: “That we believe that the said Joseph James Carter never had any intention of committing the crime of which he was found guilty, and the circumstances of the case point to no premeditation on the part of the said Carter. That the said Carter has up to the date of the said crime, as proved by the evidence, always borne the character of a steady, peaceable, quiet, and reliable man. That the said Carter was found guilty of the said crime of which he was charged mainly on the evidence of his own son, a boy of eight years of age, and therefore, it would be a matter of regret to the whole community if the sentence of death were carried out. That the ends of justice will be fully served without carryout the extreme penalty of the law.” This case was the first to be decided in Australia under new instructions to the Governor, by which it is directed that the prerogative of mercy shall only be exercised on the advice of his responsible Ministers. After about 45 minutes of consultation, Carter’s death sentence was subsequently commuted to one of imprisonment for life, with hard labour, in the Yatala Labour Prison. It seemed that the remainder of Carter’s life had been determined, but yet again, he managed to dodge his allotted punishment.

On Thursday, 28th April 1904, Before His Honour the Chief Justice at the Supreme Court, the Crown Solicitor (Mr. J. M. Stuart, K.C.), mentioned that it had pleased His Excellency to take into consideration the question of pardoning the prisoner, who had satisfied nearly 12 years of his sentence. The evidence at the trial showed somewhat strongly that the deed had been done owing to the influence of intoxicating liquors. Accordingly, the pardon would be granted on condition that the man, besides keeping the peace towards the public generally for the remainder of his life, refrained from the use of intoxicating liquors of any kind. His Honour took the recognizances of Alfred James Carter, labourer, of Broken Hill (brother to the prisoner), and Hermann John Karger, boarding housekeeper, of Broken Hill, who gave sureties in sums of £250 each for the fulfilment of the conditions for five years. The Crown Solicitor said that when the sureties had been deposited with the Government, Joseph Carter would be brought before His Honour to sign his own recognizance.

The following Tuesday, the Crown Solicitor handed to His Honor the document giving authority for release, and specified the terms of the pardon. In discharging Carter His Honor advised him to resist temptations to drink intoxicating liquors, and immediately sign the pledge. If he could always say “I am a signed abstainer”, it would be a potent reply to an invitation to drink. That was a duty he owed to loyal friends, and it involved his own safety. Carter, having promised to act on the advice, was allowed to leave the Court with his friends.

Quite a fortuitous result, considering the callous nature of the murder, and the long lasting impact on the traumatised widow and her three young children. Without a husband, life would have been precarious for Annie Edwards in the late 1800s. Fate did not smile upon this unfortunate soul. Benefactors did not come to her aid. She developed sacroiliitis, a disease that targets the hip joints, leading to bone and nerve damage. On the 11th January 1898, only 5 ½ years after the tragedy, Annie Edwards died at the Destitute Asylum, North Terrace, Adelaide, aged just 30 years. It would have been a painful and wretched end to her tragic story. What became of her children is unknown.

Researched and compiled by Jonathon Dadds, from the Campbelltown Library “Digital Diggers” group.

If you have any comments or questions regarding the information in this local history article, please contact the Local History officer on 8366 9357 or hthiselton@campbelltown.sa.gov.au

References

THE MAGILL MURDER. (1892, August 22). Evening Journal (Adelaide, SA : 1869 - 1912), p. 2 (SECOND EDITION). Retrieved October 29, 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article206512675

THE MAGILL MURDER. (1904, May 14). Adelaide Observer (SA : 1843 - 1904), p. 35. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article163046824

THE MURDER AT MAGILL. (1852, June 28). South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA : 1839 - 1900), p. 2. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article38455660

LAW AND CRIMINAL COURTS. (1892, August 6). South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA : 1839 - 1900), p. 6. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article48536089

THE MAGILL TRAGEDY. (1892, August 1). The Pictorial Australian (Adelaide, SA : 1885 - 1895), p. 3. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article230507027

SKETCHES IN CONNECTION WITH THE MAGILL TRAGEDY. (1892, August 1). The Pictorial Australian (Adelaide, SA : 1885 - 1895), p. 1. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article230507015

SHOCKING TRAGEDY AT MAGILL. (1892, June 22). Evening Journal (Adelaide, SA : 1869 - 1912), p. 3 (SECOND EDITION). Retrieved October 29, 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article204481701

SHOCKING TRAGEDY AT MAGILL. (1892, June 25). Adelaide Observer (SA : 1843 - 1904), p. 35. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article160726265

LAW AND CRIMINAL COURTS. (1892, August 5). Evening Journal (Adelaide, SA : 1869 - 1912), p. 4 (SECOND EDITION). Retrieved October 29, 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article206511400

LAW COURTS. (1892, August 6). The Express and Telegraph (Adelaide, SA : 1867 - 1922), p. 6. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article208519998

SUPREME COURT – CRIMINAL SITTINGS. FRIDAY, AUGUST 5. (1892, August 6). South Australian Chronicle (Adelaide, SA : 1889 - 1895), p. 3. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article92289978

CONDEMNED TO DEATH. (1892, August 12). Port Adelaide News and Lefevre's Peninsula Advertiser (SA : 1883 - 1897), p. 2. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article195891429

PARDONING A PRISONER (1904, April 30). Adelaide Observer (SA : 1843 - 1904), p. 39. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article163041455

TRAGEDY AT MAGILL. (1892, June 25). South Australian Chronicle (Adelaide, SA : 1889 - 1895), p. 9. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article92291270

THE TRAGEDY AT MAGILL. (1892, June 23). South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA : 1839 - 1900), p. 7. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article48230322

THE MAGILL MURDER. (1904, May 14). Adelaide Observer (SA : 1843 - 1904), p. 35. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article163046824