Fatal Affray in Paradise

On Saturday, the 18th of November 1876, James Grant Walsh, a 19-year-old man from Paradise, received injuries that resulted in his death the following morning. There were conflicting accounts of the affray he entered, and key witnesses were not brought forward for questioning. Testimony from the Inquest differed from that provided at the Supreme Court hearing, which was held over four months later. This is the tale of a trifling dispute that caused two well-meaning bystanders to enter a senseless brawl, where ultimately, the life of one human being was lost, and the liberty of another was forfeited.

James (Jim) Walsh had worked on the Saturday and was reportedly under the influence of alcohol when he came upon an unruly scene near the Paradise Bridge Hotel, Lower North East Road, Paradise, at around midnight. Richard Fullalove, a local resident he knew, was on the ground, in the act of defending himself against several attackers. Apparently, Fullalove had given notice to leave his rented premises, and despite the late hour, was in the process of shifting some of his possessions to his new house, which was directly opposite, on the other side of the road. Fullalove was also under the influence of alcohol. In response to O’Neill’s solicitor, Fullalove declared at the inquest that he had only had one or two glasses of beer the whole evening, and was quite sober when he left the hotel. Under cross-examination in the Supreme Court, he admitted that he had consumed ‘four or five glasses of ale’ in the ‘two hours’ he spent at the bar.

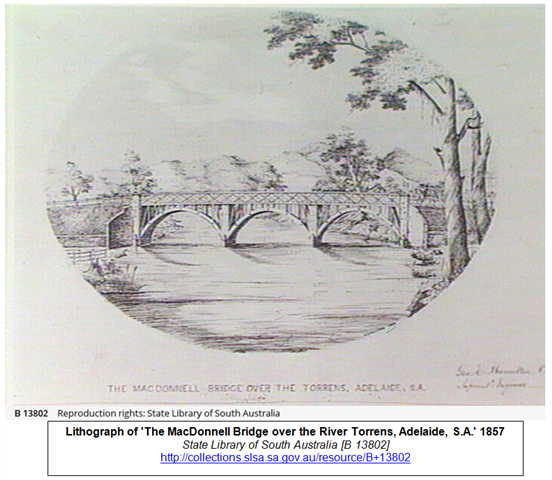

According to Fullalove’s testimony, he had enlisted the help of a 13-year-old boy, Thomas Collins, to assist him with the removal process. He took some crockery over to the new house and was on his way back when he was confronted by his landlord, William Fox, who lived at the back of Fullalove’s rented property. The most likely position of the cottage would have been on the South Eastern side of Lower North East Road, between George and Martha Streets, at Paradise. The River Torrens and the magnificent Old Paradise Bridge, also known as the MacDonnell Bridge (see lithograph copy), were a 2-minute walk up the hill, and the Paradise Bridge Hotel (see photograph) was about 200 metres down the road.

Fullalove revealed in the Supreme Court that at the time he owed Fox ten shillings (one dollar) for unpaid rent. Fox apparently refused to allow anything to be taken away until the rent due was paid. He was accompanied by his wife and children, and Felix O’Neill, his friend, who also happened to be Fullalove’s neighbour. They followed him to the house, and Fox said, “I want either your blood or money.” Fullalove understood this demand was referring to the outstanding rent, and replied that he would, as he had always done, send it by his wife, or take it to him himself.

Fox then raised a stick and hit Fullalove so violently on the chest that it knocked him backwards into the house. Fullalove ran out by another door to get help when he saw Felix O’Neill standing on his garden plot with a shovel in his hand. He asked him what he wanted and O’Neill replied, “You bloody thief, I’ll let you know what I want.” He then picked up a stone about the size of two fists, and threw it at Fullalove, who dodged the missile, ran back into the house and bolted the door. When he thought the mob had cleared away, he ventured out by the opposite door, but he had not gone far from the light of his lamp before O’Neill, Fox, Fox's two boys, and a host of children rushed upon him. O’Neill had a shovel in his hand, and Fox and the boys were armed with sticks. Fullalove retreated to his door, and seizing a broomstick he defended himself as best he could. He struck Fox with it, but before he could raise it a second time they rushed upon him in a body and knocked him down. In his dramatic recollection, Fullalove said that every time he attempted to rise they felled him again.

There were different interpretations of the exchange. According to one witness, Mrs Fox called out to O’Neill to come to her husband’s assistance, as he was ‘being murdered’, although another witness suggested it was Fullalove crying out “murder”. Walsh came upon the mad scene and Fullalove begged him to intervene. He cried out, “Jim! For God's sake come and help me. Take some of them off or they'll kill me!” Walsh responded to Fullalove’s plea, after politely, and rather strangely, asking permission to enter his property. He then rushed in, shoved Fox and his boys to one side, and attempted to help his friend. He was in a stooping posture, in the act of picking up Fullalove, when O'Neill struck Walsh on the back of the head with the shovel that he held in his hand. According to witnesses, it was quite a deliberate blow, struck in a downward ‘axe’ fashion. Walsh cried out “Oh, good God!” fell on his hands and feet, and scrambled out into the middle of the road, where he then managed to stand up. Meanwhile, Fullalove had escaped from his gang of aggressors. He saw that Walsh’s shirt was covered with blood, with his head hanging on one side as he made his way towards the bridge.

William Martin, a 15-year-old local labourer, and one of the more credible witnesses, followed Walsh and asked him what was dropping from his head. He replied “water”, but when William put his hand to Walsh’s head he found it was covered with blood. For some reason, Walsh said to William, “Don't you tell anyone, because I do not want anyone to know I received the cut”. The trio then went to a nearby friend, Mr Collins, where Walsh explained what had happened and stated that it was O’Neill that had struck him with a shovel.

It appears that Walsh then walked to the nearby house of a friend, Mr R. Martin, young William’s father. Walsh told the Martins that he felt faint after receiving a blow and asked Mrs Martin to bathe his bleeding head. She cut the hair away, dressed the wound and Fullalove apparently helped by putting a piece of paper with Bates' salve on the cut. Bates’ salve (see photograph) was an oblong stick of firm, brown waxy ointment, used as a medicated plaster for skin injuries. Although regarded as a reliable home remedy for minor cuts and abrasions, it would have been completely inadequate in this case.

Fullalove’s movements after assisting Walsh are unclear, but John Rourke, a blacksmith living at Paradise, gave evidence that around the time Walsh was recovering at the Martins, Fullalove gave him the rent money he owed Fox. This transaction occurred about 20 minutes after the affray was over, and Rourke then handed the money to Fox. Rourke was present at the fight, but his evidence was quite different to Fullalove’s. He saw Fullalove strike the first blow with a broom handle, knocking Fox to the ground. He also saw the retaliation from Fox and the subsequent intervention from Walsh. At the Inquest he said he saw Walsh receiving a blow from a ‘short piece of wood’, but could not recall what the weapon was or who dealt the blow. In the Supreme Court, it appears that he only heard the fatal blow, despite his assertion that he ‘recollected the whole affair as well now as he did when he gave evidence at the inquest’.

Fullalove completed his covert transaction with Rourke and Walsh ended up falling asleep on the Martin’s sofa. Early on Sunday morning Mr and Mrs Martin were awakened by the loud breathing of Walsh, who was by this time speechless, and close to death. At about 9 a.m. they sent their son William to Fullalove’s house to convey the news of Walsh’s rapid decline. Fullalove promptly arrived and noticed that blood was flowing freely from Walsh’s wound. He attempted to speak to him, but could not obtain an answer. Fullalove then left him, and after about half an hour Mrs Martin's little girl came to his house to say that he was dead. He went down to see the body and found that Walsh was still breathing a little, barely clinging to life.

Shortly afterwards Doctor John Benson came and examined him, and pronounced that life was extinct at 25 minutes past 10 that morning. He made a post-mortem examination of the body, and found that death had been caused by the compression of an artery. There was an incised wound on the head corresponding with the wound on the inside, and because the artery had been ruptured, he surmised that there was little that anyone could have done to save his life. In these early pioneering days, death from such an injury was a mere question of time.

Police-trooper Matthew Pascoe was then called to the scene. He examined Walsh’s body at about 12.30 on Sunday the 19th November and corroborated the medical evidence. After obtaining information from William Martin, Police Trooper Pascoe then went to O’Neill’s premises and found the shovel that was allegedly used to commit the murder. O’Neill was subsequently arrested and charged with killing and murdering with malice aforethought. O’Neill confessed his involvement and said to Trooper Pascoe, “I will tell the truth; I struck the man, I struck him to save another. When I came home last night I heard a row at Fullalove's house between Fox and Fullalove. I was looking on when I saw Fox was struck. I saw Walsh strike Fox. I picked a stick up from the ground and struck Walsh on the head. I was quite sober. I did not know who it was when I struck the blow.” Although the post mortem examination suggested that the implement used by O’Neill may well have been a piece of wood, his confession was at odds with witness statements that consistently described his weapon as a shovel or spade.

An inquest was held the following Monday, the 20th November at the Paradise Bridge Hotel. After hearing the evidence, The Coroner’s address to the Jury was melancholy and brief. He saw the case as especially painful because the unfortunate affair deprived the community of a young man just entering the bloom of life, and one who might have proved a most useful member of society. He also sympathised with the prisoner before them, because from the evidence presented there did not appear to have been any malice or hatred involved in the crime. He added that there was no question that the prisoner before the Court had done the deed, and it was the solemn duty of the Jury before God and their country to return a verdict in accordance with the evidence that had been brought before them.

The Jury were then left in the room alone, and after about 45 minutes they arrived at the following verdict: — “We find that the deceased James Grant Walsh came to his death by a blow struck with a spade, shovel, or some sharp weapon by Felix O'Neill.” A verdict of manslaughter was recorded, and O’Neill was then transferred to prison to await his trial at the next Criminal Sittings of the Supreme Court. Fortunately for the O’Neill family, his time in custody was brief and he was released on bail the following Tuesday.

At this stage, the reader may be wondering why Fox and his family were not questioned by authorities, or why he was absent at the Inquest. One of the Jurors at the Inquest asked the Coroner why Fox’s evidence was not taken, and why he wasn’t arrested as an accomplice in the affair. His understandable curiosity was dismissed by the Coroner who replied, “I have only to do with the case before me, and have nothing to do with Fox”.

The law did catch up with Fox a week after the Inquest, when he and his son Patrick were charged with assaulting Fullalove during the melee. Fullalove provided a similar story to the one he outlined at the Inquest, however the throng of children seemed to have disappeared, and Fox’s weapon had changed from a stick to a spade or shovel. Although Fullalove painted himself as the innocent victim of a violent assault, the Judge did not accept his interpretation of the events. He suggested that Fullalove certainly provoked the row, if he did not commence it, and the case was subsequently withdrawn.

The trial was eventually held on Wednesday the 4th of April 1877, and Felix O’Neill was, unsurprisingly, convicted of the manslaughter of James Grant Walsh. In reply to the usual question before sentence was passed, O’Neill said he struck the blow to save another man. He was sorry for it. He had a wife and three children, and for their sakes, he hoped that His Honour would deal leniently with him.

His Honour felt exceedingly sorry for O’Neill’s family, who were deprived of their protector and support, but he was more sorry for the prisoner himself, because in consequence of that deed he had not only lost his character and forfeited his liberty, but he must carry about with him the consciousness of having spilt the blood of a fellow creature. He also suggested that Fox was the instigator of this unnecessary quarrel, all for a paltry few shillings, which he could have recovered without any difficulty in the petty Courts.

His Honour saw no adequate grounds for any violence on the prisoner's part, for he was no party to the dispute, nor was he influenced with drink. There was no evidence that his friend Fox was in danger and it seemed that he had much the best of the encounter. It was under these circumstances that the prisoner seized hold of a dangerous and deadly weapon, and struck the deceased with a blow that resulted in his death. The deceased was not only no party to the quarrel, but was engaged at the time in an act of kindness — in rescuing the prosecutor Fullalove, who had been knocked down, overpowered by violence, and was being brutally treated. His Honour concluded that the offence O’Neill committed could not be passed over lightly and subsequently sentenced him to seven years imprisonment with hard labour.

A sad outcome for the families of O’Neill and Walsh, but fortunately for the Fox family, it appeared that William and his sons had managed to avoid any further scrutiny. Fate, however, concocted another senseless scenario some 17 years later.

On Monday 4 June 1894, newspapers reported that William Fox junior, the son of William Fox, was hurried into eternity through the accidental discharge of a gun. Young William had been on a parrot shooting expedition on the Saturday with his brother Patrick and his cousin Patrick O'Neill. When they were two miles up the road leading to Highbury they loaded their pieces, the elder brother remarking, "Be careful, Will." William, with his gun between his legs, was handing shot to his cousin when the firearm accidentally went off, the charge scraping the skin off his chest, entering his chin on the right side, and lodging in his head. Patrick Fox had his eyes averted at the time, but on hearing the unexpected report turned instantly and saw his brother prostrated on his back with blood pouring from the right side of his windpipe. Patrick called out, "For God's sake, can you speak or get up?" All William was able to ejaculate was "No," and he died almost immediately. His body was conveyed to the residence of his father at Paradise, and once again, the Coroner held an inquest at the Paradise Bridge Hotel the following Monday.

Mortality was ever present in the 1800s, and for most pioneering families, hardship and loss were a regular part of daily existence. Young William was only nineteen when he exited this world, the same age that Jim Walsh had attained when he met his untimely death. As one paper aptly recited, ‘In the midst of life we are in death’.

Researched and compiled by Jonathon Dadds, from the Campbelltown Library “Digital Diggers” group.

If you have any comments or questions regarding the information in this local history article, please contact the Local History officer on 8366 9357 or hthiselton@campbelltown.sa.gov.au

REFERENCES

A Fatal Fight. (1876, November 27). The Herald (Melbourne, Vic.: 1861 - 1954), p. 3. Retrieved August 25, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article244271555

CORONERS INQUESTS. (1876, November 21). Evening Journal (Adelaide, SA: 1869 - 1912), p. 3 (SECOND EDITION). Retrieved August 25, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197695757

LAW AND CRIMINAL COURTS. (1877, April 5). South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA: 1839 - 1900), p. 3. Retrieved August 25, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article40786271

Law and Criminal Courts. (1877, April 5). Evening Journal (Adelaide, SA: 1869 - 1912), p. 2 (SECOND EDITION). Retrieved August 25, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197699369

CORONERS INQUESTS. (1876, November 21). Evening Journal (Adelaide, SA: 1869 - 1912), p. 3 (SECOND EDITION). Retrieved August 25, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197695757

GENERAL NEWS. (1876, November 28). The Express and Telegraph (Adelaide, SA: 1867 - 1922), p. 2 (SECOND EDITION.). Retrieved August 25, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article208308564

Law and Criminal Courts. (1876, November 27). Evening Journal (Adelaide, SA: 1869 - 1912), p. 2 (SECOND EDITION). Retrieved August 25, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197695932

LAW AND CRIMINAL COURTS. (1877, April 9). South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA: 1839 - 1900), p. 3. Retrieved August 25, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article40779653

A SAD ACCIDENT. (1894, June 4). The Express and Telegraph (Adelaide, SA: 1867 - 1922), p. 2 (SECOND EDITION). Retrieved August 25, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article208981918

SHOCKING GUN ACCIDENT. (1894, June 4). South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA: 1839 - 1900), p. 5. Retrieved August 25, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article53699996

LAW COURTS. POLICE COURT—ADELAIDE. (1876, November 27). The Express and Telegraph (Adelaide, SA: 1867 - 1922), p. 2 (SECOND EDITION.). Retrieved August 25, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article208308550

MONDAY, NOVEMBER 24. (1876, December 2). South Australian Chronicle and Weekly Mail (Adelaide, SA: 1868 - 1881), p. 14. Retrieved August 25, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article92255176

CORONERS' INQUESTS. (1876, November 21). South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA: 1839 - 1900), p. 6. Retrieved August 25, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article42998880

FATAL AFFRAY AT PARADISE. —CASE OF MANSLAUGHTER. (1876, November 25). South Australian Chronicle and Weekly Mail (Adelaide, SA: 1868 - 1881), p. 10. Retrieved August 25, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article92255762

MANSLAUGHTER AT PARADISE. (1876, November 25). Adelaide Observer (SA: 1843 - 1904), p. 11. Retrieved August 25, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article159491686

SHOT BY ACCIDENT. (1894, June 5). The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA: 1889 - 1931), p. 3. Retrieved August 25, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article25726926

BATES’ SALVE. Ointment, Bates & Co. (William Usher), 1851 - mid-1900s. Flagstaff Hill Maritime Museum and Village. Retrieved August 25, 2022, from https://victoriancollections.net.au/items/52160aee19403a17c4ba247e

Photographs

Lithograph of ‘The MacDonnell Bridge over the River Torrens, Adelaide, S.A.’ 1857, [B13802] State Library of South Australia, Retrieved August 29th, 2022, from http://collections.slsa.sa.gov.au/resource/B+13802

Paradise Bridge Hotel, [B 20722] State Library of South Australia, Retrieved August 29th, 2022, from http://collections.slsa.sa.gov.au/resource/B+20722