Magill Reformatory

Magill Reformatory Timeline:

- Orphan Asylum and Industrial School, Woodforde (1867-1890)

- Magill Industrial School (1869-1898)

- Boys’ Reformatory, Magill (1891-1967) 1st building demolished 1967

- McNally Training Centre, Magill (Nov 1967-1979)

- South Australian Youth Training Centre, Magill (1979-1993)

- Magill Training Centre (1993-2012) closure and demolition 2012

Magill Industrial School 1869-1898

Photo of Magill Industrial School c.1869 - 1899 by Samuel Sweet

In 1866 with the passing of the Destitute Persons Relief Act, the government was given the responsibility of establishing an Industrial School for children who had been charged as neglected or destitute. These were terms used in the Act to refer to children who for various reasons were in need of care.

The government bought over 100 acres from the Woodforde Estate when the owner Captain Duff decided to sell it in the 1850’s. It turned out to be a good land purchase although it was criticised at the time. The intention was to build a ‘Lunatic Asylum’ but it was considered that it was too far away from town for doctors and visitors. Due to the need for a home for young delinquents, including orphans, the Industrial School and Orphanage was built on the site instead. The building was surrounded by 100 acres of property with an orchard, vegetable garden and cows kept for butter and milk.1

The foundation stone for the Magill Industrial School was laid on 21 October 1867, however no children were admitted until the end of 1869. Mr E.J. Woods, prominent South Australian colonial government architect designed the building. An article in ‘The South Australian Register on Tuesday February 2nd 1869 described the style of the building:

“It is of the Italian Gothic style of architecture, not elaborately ornamental, is of solid construction, and conveys the idea of a good substantial building intended to last for a very considerable number of years, and reflects credit upon the Colonial Architect, by whom the plans were prepared.”

In 1869 157 children were transferred from temporary accommodation at the Grace Darling Hotel at Brighton. The Magill site was at that time used as a Receiving home for State children.

The Girls' Reformatory, Magill shared the site from 1881 to 1891 as did the Boys' Reformatory, Magill from 1869 to 1880. In 1898 the Industrial School moved to Edwardstown and became the Edwardstown Industrial School. Initially both the Boys' and Girls' Reformatories run by the government were also located on the site of the Industrial School.

Despite its name, the Magill Industrial School was not an industry training school but a receiving depot for all children who had been made wards of the State. These children came from a wide range of situations and included children who had been deserted, orphaned or deemed neglected. They remained in the School until other suitable accommodation was found with a foster family, in service, or in another institution. Boys and girls who had been committed to the care of the state because of an offence, also passed through the Industrial School before being sentenced to a reformatory.2

Reformatories

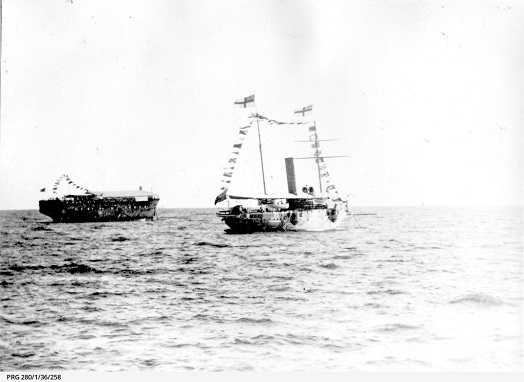

Reformatories were established in South Australia following enabling legislation in 1866–67. The first, for boys, opened east of the capital at Burnside in 1869. In 1887 the newly created State Children’s Council relocated the boys’ reformatory to the eastern foothills of Magill. Between 1880 and 1891 boys convicted of offences were sent to the Boys' Reformatory Hulk, Fitzjames, moored at Largs Bay before returning to Magill in 1891. Some boys from Magill Industrial School whose behaviour was considered unacceptable were also sent to the hulk. From 1898 the Magill Reformatory became a home for Protestant boys only. While never a part of the Magill Youth Training Centre, parts of the Catholic Church ran a Boys' Home at Brooklyn Park where Catholic boys were sent rather than to the Magill Reformatory.

The 'Protector' and 'Fitzjames', Largs Bay. State Library of South Australia [PRG 280/1/36/258]

Over the first three decades of the twentieth century approximately 200 children were annually held in South Australian reformatories. Between 1927 and 1939 a yearly average of 46 boys were kept busy with farm training and in a boot repair shop at Magill. Facilities for younger boys were opened at north-eastern Campbelltown in the 1940s, while the McNally Training Centre for boys, on the site of the former Magill reformatory, opened at Magill in 1967.3

The girls’ reformatory was originally located for most of the 1870s in the Destitute Asylum on Kintore Avenue, Adelaide prior to moving to Magill in 1881 where it was established in a wing of the Magill Industrial School. It was run by the government for girls who had committed offences or were deemed to have behavioural problems. The Girls' Reformatory, Magill closed in 1891 and girls moved to the Girls' Reformatory, Edwardstown. The Industrial School then moved into the vacated girls’ quarters.4

The Boys' Reformatory, Magill also shared the Industrial school site for two periods, from 1869 to 1880 and again from 1891 to 1967. During the mid-1890s between 30 and 40 children were accommodated in the Industrial School at one time. However, over 300 children passed through the School during the year. Space in the School was limited and overcrowding a constant problem. The Destitute Board and its successor, the State Children's Council, often complained that it did not have the appropriate facilities to educate the children placed there. Most were transferred on to a reformatory or were placed into service as soon as possible. There was also continuing concern at the Industrial School sharing the same site as the Boys' Reformatory.

Escapes

John Martin Escapes Again – as reported in the South Australian Chronicle 15 September, 1894.

“John Martin, the young desperado whose record of escapes from custody probably has no parallel, has once more yielded to the temptation to clear out, and the police are on the qui vive in the hope of capturing the “bold bad boy”. Martin is only 15 years of age. Originally Martin was sent to the Industrial School, but he absconded and was then sentenced to the Reformatory on a charge of larceny. He strongly resented his enforced incarceration in this institution and openly declared that he would not stay there. The precocious youth was known to be extremely cunning as well as clever, and he was carefully watched, but despite the unusual attention paid to him he succeeded in getting away 14 times from the Industrial School, The Reformatory and the State Children’s Department in Flinders Street. Some of his escapes from the Reformatory were accomplished in such a daring and skilful way that many people would have preferred to see the youth pardoned and assisted into some honest situation as the reward for his extraordinary pluck than hunted by the officials and returned to the State home which he so greatly abhors”.

After one of Martin’s escapes and subsequent appearance in the Supreme Court appearing before Mr Justice Bundey, he was placed under the care of Mr. Burton at his truant school in Glanville. Not long after this court appearance he ran away from the school and was quickly recaptured, however despite assurances from Martin that he would mend his ways, during a temporary absence of Mr Burton, he once more absconded. As of the date of 15 September, 1894 when the article was printed in the South Australian Chronicle he was still listed as “wanted” by the police.5

Norman Wilfred Baker (Willunga’s boy bushranger)

Norman Baker escaped from the Magill Reformatory on Saturday 11 March 1923. He had been working at a cowshed with another boy at 3.30 p.m. and was missed at 4 p.m. The search for Baker involved police on motorcycles who scouted the vicinity of the Reformatory on the Sunday evening, but without result. A posse of mounted police and a black tracker explored the hills working towards Willunga on the supposition that Baker was making for home. A tracker followed in his wake as far as Norton’s Summit, but there the tracks disappeared and no further trace could be picked up in the scrub country.

Baker was subsequently recaptured by Mounted Constable Grow near Strathalbyn on Wednesday afternoon 15 March dressed in his father’s clothes, and carrying a blanket and three knives. He said that he had been hiding in the scrub near Willunga, and had stolen his food supplies in small quantities from his father’s house. When caught, he said he was making for Langhorne Creek to get work grape picking. He confessed that he “had had very little to eat”, and it is believed that dissatisfaction with the uncertain nature of his supplies prompted “him to decide upon seeking employment at Langhorne’s Creek”. He was returned to Adelaide and the Magill Reformatory.6

Even back in the 1930's there was a feeling that the reformatory was not effective in improving boys' behaviour, and it was referred to as an institution for bad boys to make others bad. The buildings were said to be outdated, there was "undesirable mixing" between older and younger boys, staff were untrained and supervision was "more like that of a prison". The Mullighan Inquiry (2005-2008) report revealed that in 1945 the Reformatory Superintendent's biggest worry is keeping track of the boys who are inclined to sexual perversion, which for some reason seems to be more in evidence now. In the 1950's boys continued to be transferred from the Magill Industrial School to the Magill Reformatory for ‘subnormal sexual misconduct’.

McNally Training Centre Onwards

The McNally Training Centre was built in 1967 to house 164 boys aged from 15-18 who had either committed offences, were on remand, or required assessment. It was divided into six units, each with up to 16 residents. Three units provided shorter term accommodation for residents on remand and in short term secure care, while the other three housed boys committed for a period of treatment. There was also a maximum security unit for disturbed boys. While punishment was not as harsh as at the earlier reformatory, conditions were still extremely strict. Daily routine was highly regimented and absconders received particularly savage punishment.

In 1979 the McNally Training Centre was renamed SA Youth Training Centre, continuing as a secure care centre for up to 90 youths in five units. By 1983 corporal punishment was prohibited again at the centre, although children over 15 could be strip searched and placed in detention for up to eight hours. From 1993 the facility was renamed the Magill Training Centre, but increasingly concern was voiced about its suitability. The lack of privacy when taking a shower, and the use of "cages" to access the recreation area were significant complaints.

Cavan Training Centre was opened by the government in 1993 at Cavan as a purpose built secure care facility for young men aged between 15 and 18. It accommodated young offenders previously held at the South Australian Youth Training Centre which was renamed the Magill Training Centre. Cavan changed its name to the Adelaide Youth Training Centre when it became part of that new facility in 2012 7.

Preservation Committee

By 1902 there was growing doubt as to the suitability of the Magill building as a reformatory. As late as 1939 an honorary committee appointed by the government reported on the inadequacy of the building for its current purpose and in 1940 several organisations petitioned the Premier urging immediate action. More than fifty years after the first official report on the inadequacy of the building, the government proposed to erect a more up-to-date institution. This major step forward contained the recommendation to demolish this fine piece of South Australia’s early architecture. Apart from the fact that it represented the birth of South Australian child welfare, it was one of the few structures in the metropolitan area distinguishable by its outstanding architecture.

During the early 1960s plans were underway to demolish the old buildings forming the boys’ reformatory at Magill, and to update the institution.

In 1963 a committee was formed advocating the preservation of the building.

The earliest reference to be found of the formation of the preservation committee is of a letter sent to the Secretary of the National Trust of South Australia on 28 June, 1963 by a Mr. Gavin K. Langman.

Extract from Executive Minutes Meeting (presumably National Trust) held on 5/8/63. “As the building has been given a classification “B” by the Early Buildings Committee the Trust does not oppose any move for its retention”.

Numerous correspondence is recorded between the Magill Reformatory Preservation Committee and government officials supporting both sides of the argument for preservation and/or demolition of the building. A large part of the case for preservation was simply that the buildings unsuitability as a reformatory did not mean that it should be torn down. It could still be appreciated as a considerable piece of early South Australian architecture and another use could be found for the building. Potential uses for the building included an historical museum, a youth centre or a tourist and cultural resort.

Despite the best, long and concerted efforts of the committee, together with support and at times outrage from the public, the South Australian State Government, at that time led by Premier Sir Thomas Playford, recommended that the building be demolished.

The building was eventually demolished in 1967.

In November 1967, a new institution at Magill was officially opened and called McNally Training Centre in honour of Mr Frederick John McNally, Chairman of the Children's Welfare and Public Relief Board from 1946 to 1961 8.

References

- Magill Reformatory Folder, Local History Room, Campbelltown Public Library, S.A., viewed 16 November, 2017

- Find and Connect, viewed 19 October, 2017, https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/sa/biogs/SE00077b.htm

- Find and Connect, viewed 19 October, 2017, https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/sa/biogs/SE00057b.htm

- Find and Connect, viewed 19 October, 2017, https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/guide/sa/SE00066 .

- 1894 ‘A DARING YOUTH.’, South Australian Chronicle (Adelaide, SA: 1889-1895), 15 September, p. 9., viewed 16 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article92313962

- 1923 ‘BOY ESCAPEE.’, Observer (Adelaide, SA: 1905-1931), 17 March, p.24., viewed 16 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article165701507

- Find and Connect, viewed 19 October, 2017 https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/sa/biogs/SE00077b.htm

- Magill Reformatory Folder, Local History Room, Campbelltown Public Library, S.A., viewed 16 November, 2017

Photo References

- Magill Industrial School. Find and Connect Viewed 16 Nov 2017. https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/sa/objects/SD0000009.htm

- The Fitzjames. adelaidia.sa.gov.au. viewed 16 Nov 2017. http://adelaidia.sa.gov.au/sites/default/files/styles/banner_grayscale/public/images/banner/hulk_fitzjames

- 1894 ‘A DARING YOUTH.’, South Australian Chronicle (Adelaide, SA: 1889-1895), 15 September, p. 9., viewed 16 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article92313962

- 1923 ‘BOY ESCAPEE.’, Observer (Adelaide, SA: 1905-1931), 17 March, p.24., viewed 16 Nov 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article165701507

- Weekend Notes. viewed on 16 Nov 2017. http://weekendnotes.com/magill-youth-training centre/

- State Library of South Australia, Premises of the old Reformatory at Magill. viewed 19 October, 2017, https://collections.slsa.sa.gov.au/resource/B+63555