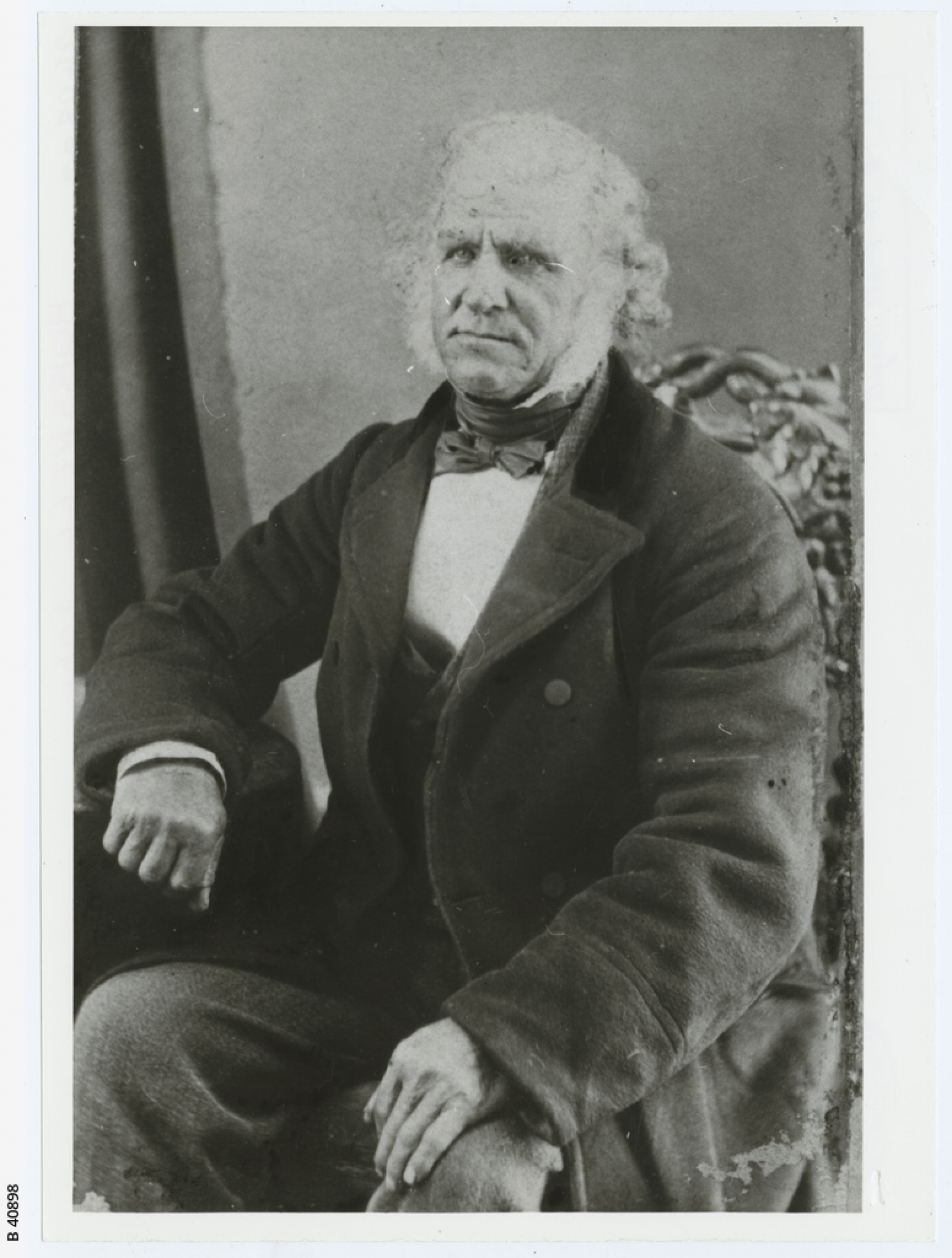

Horsnell, John - Pioneer

Arriving in Adelaide in 1839, just as the fledging city was beginning its settlement, John Horsnell was a true pioneer of this district.

Born on September 16th, 1812, in Brentwood, Essex, England, John’s early life was difficult. At the age of two, his older brothers left home to fight in the Battle of Waterloo (18 June 1815), and one year later, his father William died. At only eight-years-old, he was then ‘boarded out’ to a dairy farm at Woodvale, a township near London, with his younger brother. ‘Boarding out’ was essentially a British welfare system that placed pauper children with a foster family and paid for their care. Although the separation from his mother would have been emotionally painful, the proximity to London allowed young John to witness some of the many attractions that were on offer at the time. In the 1820s, their elder brother took the boys to see the procession for King George IV’s coronation (19 July 1821), and according to family sources, they saw public floggings, pantomimes, and the occasional hanging. Around this time (1824), the name Australia, recommended by Matthew Flinders in 1804, was finally adopted as the official name of the country once known as New Holland.

John’s mother, Mary, died when he was 17, and a few years later, his adopted parents at Woodvale succumbed to ‘consumption’ or what we now call tuberculosis. Effective treatments were decades away and during the 19th century this lethal disease was responsible for the deaths of a quarter of the adult population of Europe. Mortality rates in cities like London were particularly high, and it would have been wise to move. John married Sarah Ann Lloyd in 1838 and settled in Norfolk, but unfortunately, he contracted tuberculosis. The only help his doctor could offer was to suggest a move to the warmer climate of South Africa.

The recently married couple subsequently decided to use William Horsnell’s legacy to set out from Liverpool aboard the ship ‘Lysander’ on the 18th March 1839. Sources differ as to their intended destination, it may have been South Africa or it could have been New Zealand, where his two older brothers had already migrated. As fate would have it, the ship did not reach either of the two destinations. Smallpox broke out on board, and the Captain, William Currie, decided to bypass Cape Town. A number of the crew and many passengers, including John’s wife, died and were buried at sea. Thankfully, John was only mildly affected, but any plans of a family reunion were dashed. In the calamitous, infected environment, the Captain decided to sail for ‘Port Misery’ (now known as Port Adelaide), arriving on the 6th of July 1839.

It was the end of the voyage for John. The remaining crew walked off, leaving the passengers to fend for themselves in the recently founded city. John was quarantined at Torrens Island and when he was well enough to leave, he decided to walk to the city, as he only had 2 shillings and a sixpence to his name (about 25 cents). At this point, John had lost his parents, adopted parents and wife. He was virtually penniless, weak from smallpox, still suffering from the long-term effects of tuberculosis, and alone in a city, and a country, where he knew nobody. He soon collapsed on the side of the road, faint and bleeding.

In true pioneer spirit, James Cobbledick, another recent arrival from England, came to his rescue. James also introduced John to an acquaintance of his, Colonel George Gawler, the Governor of South Australia. John subsequently secured his first job in Adelaide as coachman to the Governor and his wife. Whilst driving Governor Gawler along Coach Road checking on the progress of surveys, he spotted a picturesque gully just south of Third Creek, near Magill. At this time, Horsnell resided at Belair and worked on the Government Farm, taking care of the horses and tending the gardens. He then moved to Waterfall Gully, where he grazed dairy cattle, prior to buying property in the same gully he had spotted earlier. He called it ‘Woodvale’ for sentimental reasons, but we now know it as ‘Horsnell Gully’. One of its key attributes at the time was its proximity to the main road from Adelaide to Melbourne. Interstate travellers would take Magill road to the Old Coach Road, then pass through Ashton, Summertown, and Piccadilly, before heading east to Victoria.

At this time, the indigenous Kaurna people would have inhabited John’s property, usually during the winter months. They used the wood and bark from the dense woodlands for fire, warmth and shelter, and ate the plentiful possums and bandicoots. In the early 1840s, John began to settle the Woodvale property. He built a house and dairy, stocked his property with animals, and began producing fruit and nuts for market. The remnants of his orchard, which included walnut trees, Osage oranges and olives, can still be seen today. He also found time to plant an English garden that included roses, violets, agapanthus, elms and oaks, perhaps in homage to the original Woodvale. The nature of his interactions with the Kaurna people is unclear, but family notes indicate that an Indigenous group lived nearby for the first 12 years of John’s settlement of the gully.

John would have had access to horses whilst at Woodvale, but apparently his preferred mode of transport into town was by foot. Although it was a two-hour walk in and a two-hour walk out, he completed this task every Sunday to attend the church service at ‘St John’s of the Wilderness’ in Halifax Street.

At age 32, John was tending to his orchard when he was unexpectedly gored by a bull. Despite the injury, he managed to walk the considerable distance to seek medical treatment from his neighbour Dr Christopher Rawson Penfold at Magill. Following his treatment, John walked back to the gully with one thing on his mind. Family documents assert that he procured a glass marble (commonly used as a bottle stopper) from a bottle in his stores, loaded his gun with it and shot the bull. The poor animal was fatally wounded, but it had done John the most remarkable favour. As luck would have it, Dr Penfold was looking for a gardener, and offered John the job of planting some grape vines he had brought to Adelaide from France. The year was 1844, and Dr Penfold named the plot ‘The Grange Vineyard’. His wife Mary proved to be a talented vigneron and the visionary manager of the Magill Estate. Future wine connoisseurs would be thankful that John knew how to successfully plant those famous vines.

Whilst working on the property, John met Mrs Penfold’s maidservant, Elizabeth Smyth, a tall, quietly spoken woman who apparently, ‘never grew upset or hysterical’. John married Elizabeth in 1848, and over the next twenty-two years, she gave birth to seven sons and seven daughters, a sizable family, but not uncommon for the times. Having fourteen children ensured that some would survive to old age and be able to look after their parents in an era where the old age pension did not exist. It was a wise decision for pioneering families. By the time John died he had outlived four of his children, another statistic that was not uncommon for the times.

In the mid 1850s, John retired from gardening at the Penfold’s winery, and lived off the rent received from his extensive land acquisitions. He focussed on cultivating his own land at Woodvale and adding, rather swiftly, to his relatively small family of four children. There may have been some tension between the early settlers and the indigenous people who used the foothills for shelter and food for 40,000 years or more. While the Letters Patent which defined the British province of South Australia included a clause recognizing the rights of the ‘Aboriginal natives’, any rights to land were obviously not honoured in practice. The process of colonisation decimated the Kaurna people as new diseases, alcohol, and loss of land took a heavy toll. Unfortunately, family notes indicate that the local indigenous people raided the wine cellar in 1854, and then left the gully, never to return.

As John and Elizabeth’s family grew, more space was required, so in 1860, he built a new stone house in the gully. The homestead and gardens must have been a wonderful sight at the time. One hundred and sixty years on, a hike through the gully reveals the remains of coaching sheds, a stable and cowsheds. Although the original dairy, the first in the state, is understandably dilapidated, the stone crafted sheds are in remarkable condition for their age. The house built in 1860 is now part of the Horsnell Gully Conservation Park and has an onsite caretaker.

John was known as a fair landlord who would assist tenants who were experiencing genuine hardship. He allowed them to cut and sell timber from his land to help them out of financial difficulties, but was quite harsh on anyone attempting to ‘put one over him’. He had no sympathy for the surveyors who trespassed on to his land and attempted to resurvey the Old Norton Summit Road adjacent to his property. Despite his age, he was not afraid of using abusive language and brute force to send these ‘rascals’ on their way, occasionally using, as the Judge in one case agreed, ‘more violence than was necessary’.

By 1871, John and Elizabeth had reared thirteen children, but like many pioneering families of the time, they also endured loss along the way. Their first son John died in infancy, and their second son James was injured during birth, which disabled him for life. Fourth son William was crippled after contracting poliomyelitis, but worse was yet to come. In 1878, Lambert, the eldest surviving son, was disabled in an accident, and in 1880, he died from tuberculosis. Two years later, his daughter Selena died of the same disease, and the following year, son William also succumbed to the dreaded ‘consumption’. John toiled on, now in his 70s, maintaining the property with the help of his wife, sons and daughters. Young son George Herbert Stanley Horsnell, born in 1869, and named after Colonel Gawler, grew into a tall and exceptionally strong man. He was the last of the family to manage Woodvale in the manner in which John had established the property.

John’s health started deteriorating in 1893 after a slight stroke. According to family notes, he became very thin and suffered lameness. The next year, he had two more strokes and required the use of a wheelchair, before a severe stroke caused a loss of speech in mid 1895. He died on Sunday 24th of November that year, aged 82, and was buried at St. George’s Anglican Church cemetery, Magill, with his departed children. Elizabeth died peacefully at Woodvale five years later and was buried with her husband.

In 1839, John Horsnell had left England with his first wife Sarah, hoping for a better life in a warmer climate. After what must have been a horrendous experience at sea, he arrived in Adelaide alone and sick, but persisted in the midst of unthinkable odds. At the time of his death, he had established a magnificent homestead for his family, owned almost 600 hectares of land, and left an estate valued at around 16,000 pounds, a figure equating to about six million dollars today. From humble beginnings, he went on to become one of the most successful pioneers of our district.

Researched and compiled by Jonathon Dadds, from the Campbelltown Library “Digital Diggers” group.

If you have any comments or questions regarding the information in this local history article, please contact the Local History officer on 8366 9357 or hthiselton@campbelltown.sa.gov.au

References

Ancestry Library Edition (2022). John Horsnell 1812- 1895. Accessed 15th June 2022 from https://www.ancestrylibrary.com.au/family-tree/person/tree/76633568/person/46347681856/facts

Horsnell, A. B. (1989). John Horsnell’s Chronological Table. The Life and Times of a Colonial Dairy farmer. Unpublished manuscript.

Walton, G. (2019). The Boarding Out System: Foster Parents in the 1800s. Retrieved June 1st 2022 from https://www.geriwalton.com/the-boarding-out-system-of-orphans-and-deserted-children-with-foster-parents-in-the-1800s/

White Hat (2022). The White Hat Guide to The Naming of Australia. Retrieved June 1st, 2022 from https://www.whitehat.com.au/australia/history/naming-australia.aspx

History of Tuberculosis (2022, May 20). In Wikipedia. Retrieved June 1st 2022 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tuberculosis#Nineteenth_century

John Horsnell (abt. 1812 - 1895) (2022). In WikiTree. Retrieved June 1st, 2022 from https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Horsnell-12

Park Friends (2013, May 13). Pioneer John Horsnell. Retrieved June 1st 2022, from http://parkfriends.com.au/more-on-john-horsnell

Simmonds, P. (2017, September 17). Horsnell Gully Conservation Park 5CP-094 and VKFF-0894. VK5PAS Amateur Radio, Short Wave Listening. Retrieved June 1st 2022, from https://vk5pas.org/2017/09/17/horsnell-gully-conservation-park-5cp-094-and-vkff-0894

O’Brien, L.Y. & Paul, M. (2013). Kaurna People. Accessed 29th June 2022 from https://adelaidia.history.sa.gov.au/subjects/kaurna-people

Pathon, T. (2014). Kaurna People. Accessed June 29th from https://troypathon705.wixsite.com/hendonkaurnagarden/portrait

Mary Penfold. (2021, December 13). In Wikipedia. Retrieved June 1st 2022 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Penfold

Bishop, G.C. & and McGowan, R. (1985). Tier on Tier: A History of Basket Range. Investigator Press.

Officer L.H., & Williamson, S.H. (2022). Measuring Worth. Computing 'Real Value' Over Time with a Conversion Between U.K. Pounds and U.S. Dollars, 1791 to Present. Retrieved June 16th 2022 from https://www.measuringworth.com/calculators/exchange/result_exchange.php

South Australia. Department of Environment and Natural Resources (2010, October). Horsnell Gully Conservation Park and Giles Conservation Park. Healthy Parks Healthy People. Retrieved 19th June 2022 from horsnell_gull___giles_cp_brochure.pdf

Trove Articles

POLICE COURTS. (1862, May 2). South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA: 1839 - 1900), p. 3. Retrieved June 19, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article50170897

ADELAIDE: TUESDAY, DECEMBER 5. (1865, December 9). Adelaide Observer (SA: 1843 - 1904), p. 4. Retrieved June 19, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article159499577

POLICE COURT—ADELAIDE. (1862, May 2). The South Australian Advertiser (Adelaide, SA: 1858 - 1889), p. 3. Retrieved June 19, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article31810082

Family Notices (1900, April 19). South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA: 1839 - 1900), p. 4. Retrieved June 19, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article56548364

FARM AND STATION. (1893, May 27). Adelaide Observer (SA: 1843 - 1904), p. 3. Retrieved June 19, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article160808738

LATEST NEWS. (1896, February 21). Evening Journal (Adelaide, SA: 1869 - 1912), p. 2 (SECOND EDITION). Retrieved June 19, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article199887215

POLICE COURT. (1848, November 11). Adelaide Observer (SA: 1843 - 1904), p. 4. Retrieved June 19, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article158926739

GENERAL NEWS. (1895, November 30). Adelaide Observer (SA: 1843 - 1904), p. 30. Retrieved June 19, 2022, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article161831375